Greasy air oozes out when we open the door to the truck stop cafe. Cigarette smoke, grilled hamburgers, burnt hash browns, and perked coffee replaces the frosty air outside. Men in plaid wool shirts hunch over thick white ceramic plates of food, heavy jackets draped over chair backs. Ashtrays hold smoking butts. A few people, traveling through on their way to somewhere north, as we are, occupy red leather booths. There are few women.

Relief hangs in the room along with the greasy air. Everyone, apart from the people who live and work here, has braved the long slow climb up the mountain to arrive at this haven. The bright cafe is the only place to replenish before tackling the equally treacherous descent a few yards beyond the cafe. .

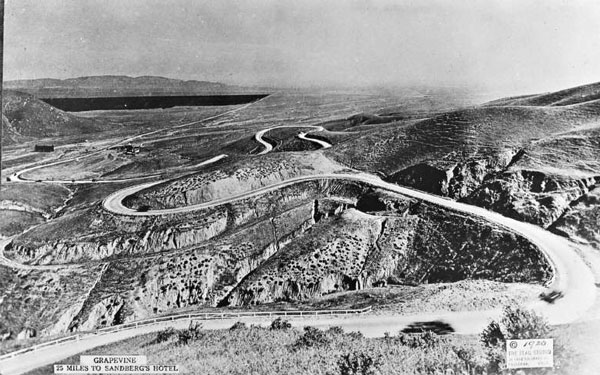

It perches at the summit of Tejon Pass on the section of the Ridge Route, now Highway 5, which used to snake through the Tehachapi mountains in Southern California. It’s also known as the Grapevine, not because of serpentine curves it once had, but because wild grapes grew on the hillsides.

It had been a grueling, five and a half mile ascent. It’s early spring, and my family and I are on our way to see Uncle Joe and Aunt Kay in Grant’s Pass. The snow, unseasonably late, is falling faster than the windshield wipers on our old Plymouth can remove it. I’m crouched in the back seat, hugging myself, not uttering a peep. afraid any sound from me will trigger the tension in the car to explode, hurling us to the bottom of the canyon.

Through the snow and fog I glimpse cars and trucks stopped at the side of the road, radiators steaming. The long ascent of the pass has been too much for them, but my Dad is too well-versed in mechanics to let that happen to us. We will be alright.

My Dad has my unconditional trust. . He always knows how to fix things that are broken, no matter what it is, the car or a chair or a broken doll. He doesn’t complain about anything – at least not in my hearing, and I’ve never known him to be defeated by any challenge. This palpable anxiety scares me. He hunches over the steering wheel, peers through the snowy windshield, while Mother presses her head forward, Sphinx-like. She is silent, like me.

When we finally arrive at the summit after what seems like forever, he crosses his arms and leans forward on the steering wheel, his head on his arms. He takes a deep breath or two, then opens the car door. I open my door, too, and cold air bites my face. Mother commands me to fasten the buttons on my jacket before I get out. Daddy stretches his arms, arches his back, then reaches for his jacket and puts his on, too, buttoning it against the cold.

He retrieves a pack of Camels from his front pocket, taps it against his other hand to push out a cigarette, then lights it with his Zippo. The exhaled smoke mixes with the frosty air to create a fog of visible release from his cramped driving position, then he locks the car, puts the keys in his change pocket and jingles them, as he always does, a gesture that I, in my 6 year old mind, find reassuring.

To the tune of Daddy’s jingling, we enter the sanctuary of the Summit Cafe.